The Recession Hidden in Council Tax

How the unfairness at the heart of the Council Tax may be affecting you and how a disturbing rise in missed Council Tax payments may be a sign of a coming recession.

Image Source: Unsplash

There’s a disturbing trend emerging in Scotland’s Council Tax data that makes me think that we’re at risk of tipping into a recession or, at the very least, the last one never really ended for some people.

I was recently doing one of my really geeky deep dives into Government statistics spreadsheets (as one does) because I was thinking about our own proposal for a Property Tax. When we published that in 2021 it was based on the then-latest figures for housing data up to 2019.

Our proposal is that instead of a banded Council Tax based on what houses were worth in 1991, we should base our Property Tax on what a house is worth right now and that if a house is worth ten times as much as another, then it should pay ten times as much tax. Right now, a £3.5 million Band H mansion only pays about one and a half times as much as a £350,000 Band F house and only three and a half times as much as a £35,000 Band A flat.

As part of that study we worked out what the “revenue neutral” rate for the Property Tax would be if Scotland implemented it at a single national rate (in reality, Local Authorities would have the power to set their own rates) but wanted to raise the same amount of total revenue as the current Council Tax. We estimated that that value would be about 0.63% of the house’s value based on 2019 prices.

This means that the couple crammed into the £35k flat would see their Council Tax drop by almost 80%, the family in the Band F home would pay about the same as they currently do and the owner of the mansion would pay about £18,000 a year more in additional Property Tax for their luxury (plus more if they own any additional properties elsewhere).

I was asked at a recent event though if I thought that 0.63% number was still useable given that it’s half a decade old now and property prices have been rising. On stage, I could only honestly answer that it does need updated but that I didn’t have the figures to hand. As is my habit whenever I’m asked a question I can’t immediately answer though, I decided to find out.

My guess was that as property prices have been increasing then the 0.63% figure should come down a bit to maintain “revenue neutrality” (in reality, if we had had the Property Tax since 2019, it would have acted to prevent much of the price inflation we’ve seen since then and would have helped to keep housing more affordable but, alas, the Scottish Government continues to refuse to reform Council Tax and has even broken its 2021 manifesto commitment to hold a Citizens’ Assembly on local tax reform).

What I actually found in the statistics was that while house prices have gone up, the recent rises in Council Tax – as unfair and as regressively disproportionate as they are – actually seem to have compensated for the house price rises. The “revenue neutral” point for our Property Tax remains at about 0.63% nationwide.

This means that you can still very easily multiply you house’s value (if you know it, or if you estimate it using something like Zoopla’s price estimate tool) by 0.0063 to see what you would pay if we had a fair and proportionate system of property taxation in Scotland. Let me know if you try this and whether or not you think you’d save money. As I pointed out in my article about this last year, people tend to have a very skewed idea about who the “winners and losers” would actually be if we changed to a fair tax and that skewed idea is pretty much the single reason why we don’t have one.

“For most, “keep a roof over your head” is pretty high up on those priority lists as is “pay your taxes” but once you’ve already cut out your “discretionary” spending and cut back on “essentials” like food or even on energy bills, I can understand why things like Council Tax payments might be next.”

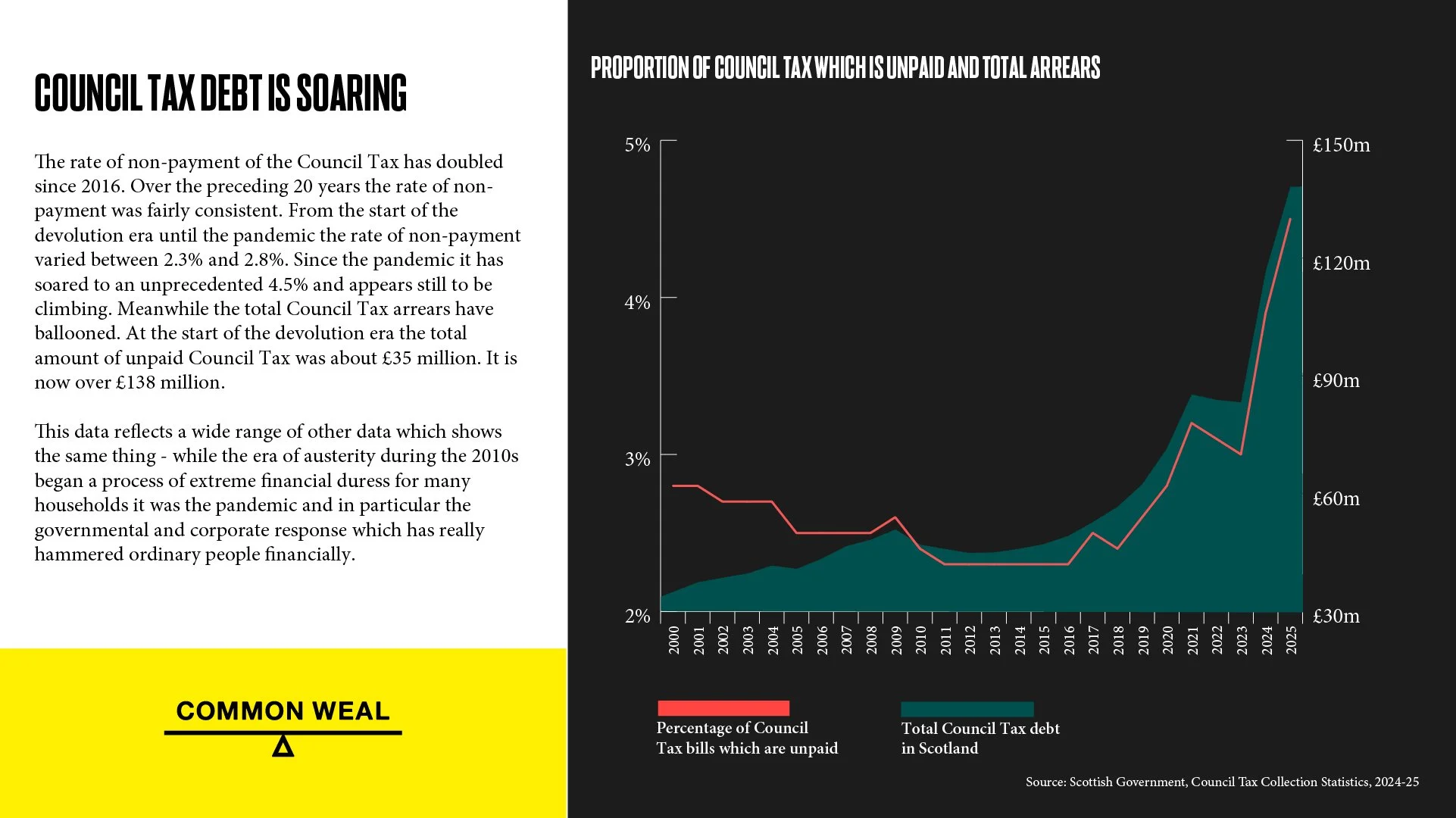

Something else came out of my deep dive into the data though. There’s been a concerning drop in the number of people falling behind in their Council Tax payments.

The numbers are still relatively small – more than 95% of Council Tax owed last year was paid – but the unpaid collection rate now stands at 4.5% and this is the largest non-payment rate since the start of devolution. As it currently stands, unpaid Council Tax bills from last year stand at around £138 million.

This spike in non-payment also doesn’t appear to be a one-off but as part of a trend starting in around 2015. I don’t believe that this is connected to the dropping of the Council Tax freeze as it predates that (though it may have exacerbated things) nor as a result of the pandemic for the same reason (though the way that the top 1% used the pandemic to harvest all of our wealth definitely happened too) but I think this may well go back to the Austerity that began in 2010.

Since then, standards of living in Britain have been steadily dropping and people have been continuously squeezed. When budgets come under pressure, people start making choices about how to ration what little they have. For most, “keep a roof over your head” is pretty high up on those priority lists as is “pay your taxes” but once you’ve already cut out your “discretionary” spending and cut back on “essentials” like food or even on energy bills, I can understand why things like Council Tax payments might be next.

The coinciding of this spike in Council Tax arrears and with energy debt and with other markers of the pressure on poorer people like food price inflation are all mounting up and we’re going to start seeing the effects of that hidden recession sooner or later even if only as the drop in Council Tax revenue starts impacting public services. £138 million is not a trivial amount in already strained Council budgets and may cause even deeper cuts to public services that are relied upon by the people who are struggling to pay their Council Tax – which will only send them even deeper down the poverty spiral.

The solutions are there – not just in reforming this badly outdated tax into something fairer, but also by aggressively tackling the causes of poverty. We need better wealth taxes in general, more public ownership over critical sectors like housing and energy and just generally an economy and society that places more emphasis on all of us than on watching the GDP line go up. Because if this data keeps going the way it seems to be going, that line may soon start to go the other way instead.